SUN-12

Sunder Nagri, Part II

Oct. 13th (Part I was on the 8th)

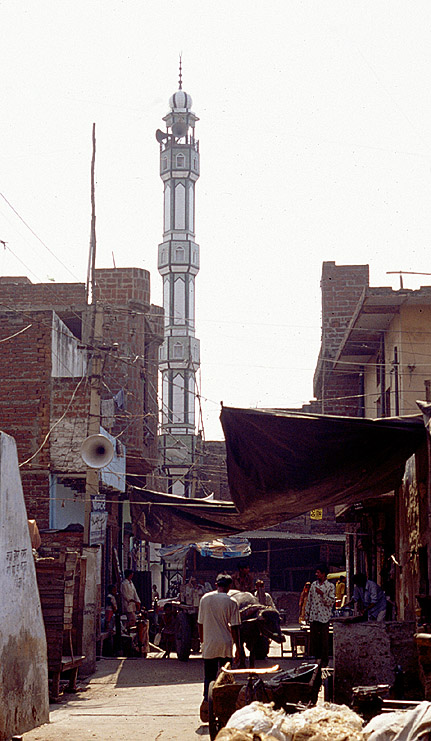

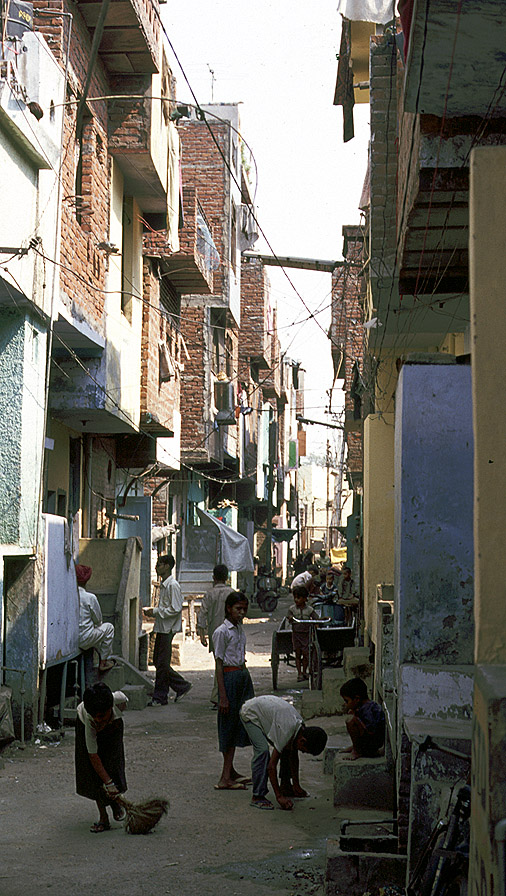

I returned to Sunder Nagri yesterday. I went there in a day-hired taxi and we

had some difficulty finding the St. Stephen's Dispensary among the kilometers

and kilometers of chaotic and dirty streets.

Zahir and I talked for several hours on the shaded roof of the Dispensary, and he explained to me his background: His father came from Bengal and his mother from Old Delhi. They married as traditional Moslems, and the father worked for many years as a relatively succesful auto mechanic in Seelampur in East Delhi. His shop employed 12 people and they even had a domestic for the family at home.

|

|

SUN-12 |

After achieving this success, the Bengali patriarch of the family, Zahir's grandfather, demanded that they return to Bengal. Zahir's broken English made it difficult for me to understand the dynamics of the situation, but it sounded as if the patriarch saw Rupee signs in the eyes of his son, and wanted him to bring the wealth back.

The move was basically a disaster for Zahir's family, and they lost most of their wealth over the course of 1.5 years in Bengal. Then, his father, who was fed up with the ordeal, moved the family back to Delhi. He attempted to re- establish his business, but he couldn't establish the same foothold, and went bankrupt on one of his shops. His father also put up a very large sum of money for his brother to go to Mukhat in Saudi Arabia to work. His brother absconded with the money and they never heard from him again.

|

|

SUN-13 |

In the end, they ended up in Sunder Nagri/Nadna Nagri. They live in a 1-room mud-brick abode. The cooking is done with a small kerosene stove using aluminum pots, and the dishes and bathing is done at a water pump nearby. The mother spends her free time reading Quranic verses, and everyone in the family prays regularly. The parents sleep on a thin-mattressed bed, and Zahir and his 2 siblings sleep on a reed mat on the floor.

|

|

SUN-14 |

Zahir took me around the main market. There were vendors selling fruits and nuts from tables mounted on rickshaw chassis, and they would line the streets hawking their wares. Some of them had some sort of smokers to ward of the flies, which generally swarmed on any foods. The sweet seller, in particular, had to cover his chunks of honey/sugar in plastic sheets to keep the flies off. Most of the shoppers were Moslem women, who wore dresses that incorporated veils, but were very brightly colored in blue or orange or yellow, as if they were Rajasthani Hindus.

|

|

|

SUN-15 |

|

Zahir took me into the meat market, which was a dark, cool alley behind the main market. It stretched for about 2 American city blocks, and it had all sorts of meat vendors -- chicken, beef, (no pork, of course), fishes (some live), lamb, goats, and a dozen different cuts. There were HUGE SWARMS OF FLIES EVERYWHERE, landing on the unrefrigerated and unpackaged meats. The vendors were all boys about my age... some of them were shy, and some of them were very curious at my presence, and some of them were friends of Zahir and asked for their photos among this unsanitary mess. Most of them were squatting barefoot on their meat tables with their bloody cleavers next to them, and they seemed immune to the flies. The odd thing about the market is that it was completely covered in red tarp, and so everything and everyone glowed red underneath.

|

|

SUN-16 |

Zahir took me to prayers at the local mosque. Inside it was clean and calm and cool. There was a long, sink/basin like structure that had about 20 faucets, and all of the 40 worshippers there for 2PM prayers rolled up their shirts and pants and washed their feet and hands vigorously, and even girgled water in their mouth and spat it out. They all wore little white caps, and their attire was a fairly bland Moslem dress that I've seen in many photos. This crowd, as the mosque-going crowd, was more conservative than the general public, and it showed in their long peppery beards and their highly ritualistic praying. There was something going on with regards to younger Moslems moving into the sunny courtyard after a while and doing their prayers from outside, as if were some sort of pennance. Afterwords, about 10 of the bearded elders gathered around and talked to me via Zahir. They asked about my views of India and the neighborhood. They seemed friendlier than the younger Moslems at the mosque, but I don't know if this was just my percerptions or proof that their age and experience had made them more mellow to visitors. It was a vague reinforcement of my foreign policy view that the US would be better off developing relations with moderate conservative Moslems in Pakistan and elsewhere rather than trying to sideline them through Musharraf.

|

|

SUN-17 |

As Zahir and I talked, we went to a small park. There, we came across a somewhat fat and somewhat clean man about 22 years old, who asked if I was American and bugged me to take a photo of him. When he went away, Zahir appeared nervous and urged me to leave the park because "some people would be coming." Zahir was behaving very oddly, and I finally agreed to leave the park and go to another park, but my understanding was that there would be a Hindu prayer session. Zahir later told me that he knew the fat man we met, and he said that he was a thief and mugger and that he was bad news. Zahir explained that the man was protected by the police, and it was then that I got a full whiff of the smell of corruption. I personally did not see any danger, partly because there were a normal people and families around in the park at that time, but Zahir immediately recognized who he was and really wanted to get out of there.

|

|

SUN-18 |

Zahir also told me about himself: From age 14, he went to school at the Dispensary, and became a personal tutor for the younger kids. There are about 10 such tutors at the dispensary who are from the neighborhood, but Zahir showed a long-term commitment, and so the administration at St. Stephen's decided to take him under their wing. They provided him with a special but very small salary, and sponsored his studies for getting a BBA. Dr. Amod plans on having Zahir heading some co-op ventures for local crafts people. The designs of these co-ops are rather complicated, but the basic purpose is to help the people of the neighborhood by organizing their employment for them. For example, when I came last Wed., there was a group of about 8 women who were making food pouches from newsprint using animal fat. The idea is that shops would rather use these env-friendly bags rather than plastic bags.

|

|

SUN-19 |

I have to emphasize to you the importance of the last paragraph: St. Stephens and the other, better-organized and more experienced charitable organizations have concluded that the most effective charitable service that can be provided is to help with employment, rather than pouring money down the medical care sinkhole. Indeed, Dr. Amod is a general practioner, but he spends most of his days doing administrative and business work rather than seeing patients. This has important implications for whatever I may do in the future.

|

|

SUN-20 |

The WHO and MSF and other organizations do great work, but they often lack the long-term committment and grass-roots organization needed to build a sustainable program. Missionaries and hospitals like Holy Family also have made contributions and they recognize the need for providing economics-based aid (i.e. finding employment), but they lack the vigour and drive of the St. Stephens community. The government also does very little, but generally co- operates with St. Stephens in terms of getting OKs, partly because it is older than the Indian government itself and partly because it has a stellar reputation for secularism. Indeed, most of the staff is either Hindu or Moslem, but they are full of these pan-deist ideas, and even Zahir deliberately used the Christian word "God" rather than "Allah" when talking with me.